Every organization eventually outgrows its systems, and if you are reading this, you’re likely no stranger to technical debt. Our organization didn’t just outgrow our document management system; it was nearly 15 years out of date. Users had to RDP into the server to view a file. There was limited API support, no integration with our policy administration system, and no way for other tools to access documents programmatically. When we asked the vendor about modernizing, they quoted us roughly $25,000 to purchase a new version, plus $5,000 a year in maintenance costs. None of that included migrating our existing data to the new system we were being sold.

So we built our own. It took about four weeks–one week of design, two weeks of development, and one week of testing. The system now houses over 634,000 files, serves 15-20 concurrent users internally, and integrates with everything from our policy administration system to desktop scanners to Microsoft Word. This article walks through the architecture, the tricky parts, and the lessons learned along the way.

The Problem

Before this system, we had several compounding issues:

- Concurrency limits: The legacy system only supported two concurrent users. In an office with staff regularly needing to look up correspondence, this meant waiting for someone else to log out before you could get in.

- No remote access: The system required an RDP session to a machine able to communicate with the host server.

- Limited integration: Our policy administration system could surface linked documents, but did so through a clunky query against the legacy system’s COM component. We couldn’t upload docs through that route, and our other tools and applications couldn’t use it at all due to licensing constraints and COM-based integration issues. The software was so out of support that we couldn’t find much detail on how to use it if we wanted to.

- Compliance pressure: Our organization has document retention requirements that have to be met. Meeting those requirements with a system that offered no modern search and a two-user ceiling was increasingly untenable.

The core problem wasn’t that we needed a fancier UI, even though I wanted one. We needed a document management system that could participate in our broader ecosystem–something other systems could talk to, something users could access easily without fighting user limits, and something we actually controlled.

Architectural Overview

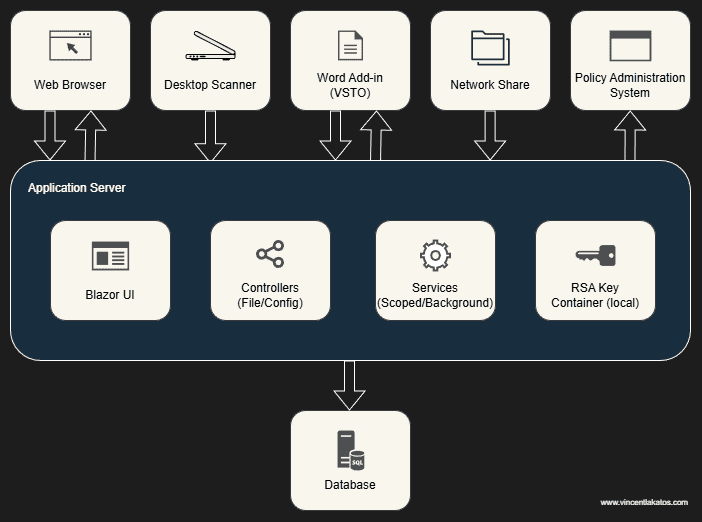

The system has six main components:

- Database: SQL Server, acting as the system of record for files, metadata, metadata types, and file types.

- UI: A Blazor Server application providing file upload, search, metadata management, file history, and document viewing.

- File API: A RESTful endpoint for uploading files, searching by metadata, and checking for duplicates. This is the primary integration point for external systems.

- Configuration API: A RESTful endpoint exposing file types and metadata types to external consumers.

- Dropbox Upload Service: A background service that monitors a network share for files paired with

.metafiledescriptors, then ingests them into the system. This originally served as a fallback for processes that couldn’t leverage .NET, but now only serves as a fallback for processes that can’t make HTTP calls. - Scoped Services: File Service (CRUD operations and duplicate analysis), ConfigurationService (metadata and file type management), StatisticsService (upload, edit, and attribution metrics), and ThemeService (light/dark mode preferences).

The design philosophy mirrors what drove the monitoring system I wrote about previously (you can find that here): dead simple integration. Any process that can make an HTTP call can upload and search for documents. Any process that can write to a network share can use the dropbox service. The barrier to entry is intentionally low.

How Documents Flow Through the System

One of the early design goals was to make it easy for documents to flow into the system from as many sources as possible. We ended up with four distinct ingestion paths, each serving a different use case.

Manual Web Upload

The most straightforward path. Users access the Blazor application, fill in metadata, provide a file name, and upload it through the browser. The process checks for duplicate files before uploading, and if files are found, the user is prompted to review those matches before proceeding. This handles any ad hoc document storage, such as scanned mail, one-off correspondence, etc.

Desktop Scanning Application

We built a standalone desktop application that communicates with the user’s scanners via the TWAIN standard using NTwain. The application captures the scanned images, lets the user preview them, attach metadata, and then upload the file to the File API with the same potential duplicate check as manually uploading the file via the web. This replaced the old workflow of scanning to a folder and manually importing files to their respective place–a process that took several minutes per document and was error-prone, sometimes resulting in documents being misfiled.

Word Office Plugin

A VSTO add-in for Microsoft Word that lets users upload the current document directly to the system without leaving Word. It uses the fax print driver on the machine to render the document to TIFF, stores it locally, and then opens an upload form that mirrors the scanning application’s interface. Users can preview what’s about to be uploaded, fill in metadata, and submit it via the File API. Same as the web upload and desktop scanning application, the user is prompted if potential duplicates are detected.

Dropbox Upload Service

A background service that monitors a designated network share. Originally, this was designed to work with external processes that couldn’t consume WCF/SOAP services or that couldn’t work with the .NET framework. After our upgrade to .NET 10, this service really just remained for external processes that can’t make HTTP calls–legacy scripts, third-party tools with limited integration options. Processes can use this service by dropping a file alongside a .metafile descriptor containing the desired file name, metadata, and file type information. This service then picks up the pair, validates the contents, and ingests the file into the system. It’s not exactly elegant, but it solved a real problem for processes that otherwise had no path into the system other than manual intervention.

Policy Administration System Integration

Documents don’t just flow in. Our policy administration system queries the File API to surface related documents directly within the policy view. Users see basic details such as file name, description, and upload dates, along with a quick link that opens the full document in their browser. This was probably one of the most impactful integrations. Staff no longer had to context-switch between the PAS and document management system to find correspondence tied to a policy (and they didn’t have to wait for fellow coworkers to exit their session).

File Isolation and Per-File Encryption

This was probably the hardest part of the system to get right and the part I’d most likely reconsider if I rebuilt the system.

We made a design choice early on to encrypt every file individually rather than relying on database-level encryption like TDE or column-level encryption. The reasoning was straightforward: if an attacker gained access to the raw data, each file would require its own decryption key. Compromising one file wouldn’t compromise all 634,000 files.

How It Works

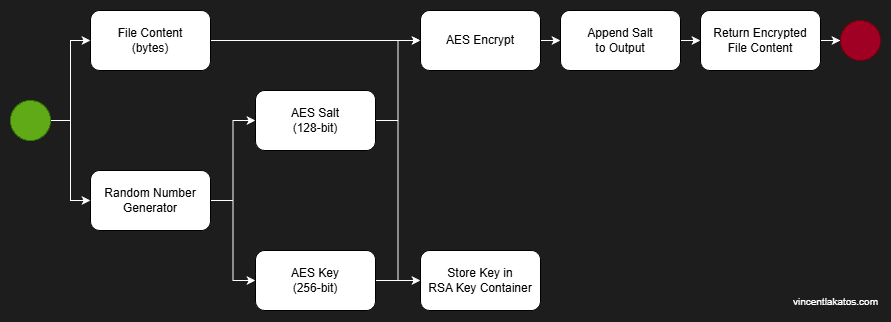

The encryption flow uses a hybrid RSA + AES approach:

//

// Pseudocode Example - Don't Use!

//

public byte[] EncryptFile(Guid fileId, byte[] fileContent)

{

// Generate a unique key and salt for this file

byte[] key = new byte[32]; // 256-bit

byte[] salt = new byte[16]; // 128-bit

using (var rng = RandomNumberGenerator.Create())

{

rng.GetBytes(key);

rng.GetBytes(salt);

}

// Encrypt the file content with AES using the generated key and salt

byte[] encryptedContent = AesEncrypt(fileContent, key, salt);

// Store the AES key in the RSA key container

byte[] encryptedKey = RsaEncrypt(key);

StoreEncryptedKey(fileId, encryptedKey);

// Append the salt to the encrypted content for later retrieval

byte[] result = new byte[encryptedContent.Length + salt.Length];

Buffer.BlockCopy(encryptedContent, 0, result, 0, encryptedContent.Length);

Buffer.BlockCopy(salt, 0, result, encryptedContent.Length, salt.Length);

return result;

}

For each file: a RandomNumberGenerator produces a unique AES key and salt. AES encrypts the file content using that key and salt. RSA encrypts the AES key, which gets stored separately. The salt is then appended to the encrypted file content byte array so it can be retrieved during decryption without an additional lookup.

Decryption reverses the process: extract the salt from the end of the byte array, retrieve and RSA-decrypt the AES key, then AES-decrypt the content.

The Tradeoff

This approach has a distinct caveat: the RSA key container is stored locally on the application server. That means only the server where the application runs can decrypt files. If we ever needed to scale horizontally (i.e., additional web servers behind a load balancer), we’d need to rearchitect the key management. Options would include a centralized key management service or migrating to SQL Server’s column-level encryption. For a single-server deployment serving 15-20 users, the current approach works and provides genuinely strong per-file isolation.

Other Interesting Problems

Duplicate File Detection

As the system grew, duplicate uploads became a real problem. Users would accidentally scan the same correspondence multiple times, or two users might independently process the same document via manual upload. This resulted in frequent manual audits that were both time-consuming and tedious. To combat this, I implemented a duplicate detection system that checks for matches based on a combination of file size (with a small percentage range), file type, and metadata markers.

The natural question here is: why not just hash the file and compare? I asked myself the same thing when I first approached the problem. The issue is that the majority of our documents are scanned images of physical correspondence. The digital representation of a scanned document can vary based on several factors, such as scanner model, pixel density, automatic rotation or deskewing, and color depth, all of which affect the byte structure just enough that two scans of the same document will rarely produce identical hashes. A size-plus-type-plus-metadata approach isn’t as precise as content hashing, but it catches the vast majority of real-world duplicates while remaining fast enough to run inline during upload.

The File API exposes a dedicated duplicate check endpoint that both the web interface and external consumers can call before committing an upload. The scanning application and Word plugin both use this to warn users before they upload something that likely already exists. Since implementing this, the duplicate scanning issues we were dealing with have been almost eliminated.

Staleness Detection

With the potential for up to 15-20 concurrent users, we had to account for simultaneous edits. If two users open the same document at roughly the same time, the second save shouldn’t overwrite any changes made by the first. We implemented staleness detection that checks whether the record has been modified since the user loaded it. If it has, the save is rejected, and the user is prompted to refresh and reapply their changes. It’s a simple optimistic concurrency pattern, but it prevents a class of bugs that would otherwise make me want to cry.

Query Performance with Stored Files

One of the design decisions I made was to store files directly in the database as opposed to storing them on disk. That said, this obviously has performance concerns: you don’t want to pull 634,000 encrypted byte arrays into memory when someone searches for a document. We handle this with projection–the file content column is only ever included in queries that actually need it. Specifically, only the GetFile(Guid fileId) and FindDuplicateFiles(FileModel file) service methods load the byte array. The GetFile method is scoped to a single record by that point and FindDuplicateFiles has already narrowed candidates by size and type before touching content. Every other query–search results, listings, metadata–projects only the columns needed for display, keeping queries fast and memory usage predictable.

Build vs. Buy

We didn’t set out to build a document management system from scratch. The original plan was to upgrade the old system to something modern, but the vendor’s pricing didn’t work for us–roughly $25,000 to purchase plus $5,000 a year in maintenance–and they couldn’t integrate with our existing systems and tooling. We’d have to build that integration ourselves regardless. When we asked about data extraction to evaluate alternatives, it became clear that leaving their ecosystem wasn’t going to be cheap or easy either.

At that point, we stopped evaluating other options. A few things became quite clear to us:

- The vendor’s cost was steep.

- Our data was in their system, and we needed their cooperation to get it out (or we had to get creative).

- Building our own solution gave us full control over integration, something we’d have to build ourselves.

We were also in a position where building a replacement was realistic. We had an experienced .NET development team, an existing SQL Server infrastructure, and enough institutional knowledge about our document workflows to design something purpose-built without months of requirements gathering. Not every team has that. If we didn’t have the skills or infrastructure readily available, this system and write-up wouldn’t exist. For us, the pieces were already there, but there was just one hurdle we had to overcome.

The hurdle: the data. We had nearly 400,000 documents locked in the legacy system with no straightforward export path. The vendor wasn’t going to help without additional cost, and their modern tooling didn’t support our ancient installation. However, the application server hosting our PAS still had a valid license for the legacy system’s COM API. I wrote a migration tool that leveraged that installation to programmatically extract documents with their associated metadata, and we ran the migration incrementally over about three months to ensure nothing was lost along the way. Once the extraction was validated, the legacy system was decommissioned.

The four-week build investment has paid for itself many times over compared to the vendor’s annual maintenance alone. By building to suit our needs, we managed to keep it lightweight, performant, and geared toward solving our specific problems rather than paying for a general-purpose system we’d have to customize anyway.

The Stack

For those interested in the implementation details:

- Framework: Originally built as an ASP.NET WebForms application on .NET Framework 4.6.2. Later upgraded to Blazor Server on .NET 10–a migration that took about two weeks once we got fully into it.

- Web UI: Blazorise component library for Blazor + custom components.

- Desktop UI: WPF + custom controls.

- Database: SQL Server with Entity Framework Core.

- Scanning: NTwain for TWAIN-standard scanner communication in the standalone desktop application.

- Word Integration: VSTO add-in using the Microsoft fax print driver for document-to-TIFF conversion.

- Hosting: IIS on Windows Server.

- Languages: C# for backend and services, minimal JavaScript for UI interactivity.

Closing Thoughts

The decision that shaped this project more than any other was per-file encryption. It provides strong isolation–each file requiring its own key, and there’s no single secret that unlocks everything. This also ties the system to a single server, which limits scaling options. If I were building this again, I’d seriously consider SQL Server’s column-level encryption or centralizing key management with something like Azure Key Vault. The per-file isolation is valuable, but the operational constraint it introduces is the one thing I’d most want to revisit.

The system started as a cost-driven decision to avoid a $25,000 vendor purchase, but it’s become something more than that. Having full control over the API means any system in our ecosystem can store and retrieve documents. Having the Dropbox service means even systems with no HTTP capability have a path in. Having the Word plugin and scanning app means users rarely need to leave their current workflow to manage documents.

It’s been running for close to 6 years now with minimal maintenance and currently houses over 634,000 files. If you’re facing a similar situation, the barrier to building your own might be lower than you think. The hardest part really isn’t the document management itself… it’s getting your data out.